Victoria Nuland resigned from the State Department in March 2024, a year ago.

Over her career, Nuland built a reputation as a hawk of hawks, having worked as an aide to Vice President Dick Cheney and as spokeswoman for Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Even before her tenure as President Joe Biden’s undersecretary of state for political affairs, Nuland was widely seen as an avatar of the United States’ post–Cold War tendency to spend billions intervening in remote foreign conflicts.

Nuland is also the wife of historian Robert Kagan, seen by many as the godfather of modern neoconservatism. Kagan’s public profile is immense. He recently appeared on a program with Weekly Standard founder William Kristol in which he bemoaned the United States’ clear lapse into a dictatorship (his framing). But some in the new Trump Administration—which considers itself antithetical to not only the Biden and Obama presidencies, but also the Bush set—are concerned Nuland’s (and perhaps Kagan’s) sway over the government is far from extirpated.

Enter Bridget Brink. Brink is the current ambassador to Ukraine—an unusual Biden holdover for such a key position. Her portfolio is, of course, under fresh scrutiny following the president and vice president’s startling throwdown with Ukrainian leader Volodymyr Zelensky last week in Washington.

Brink is a career Foreign Service officer. Civil servants are, of course, officially nonpartisan. But many civil servants develop—especially further along in their careers—unofficial alliances with certain politicians and their perspectives. Few deny this.

For several years, before becoming ambassador, “Brink was my deputy assistant secretary for Ukraine,” Victoria Nuland said in a transcribed interview with the Senate Homeland Security Government Affairs Committee. And some Ukrainian press reports friendly to the Biden administration indicate Nuland likely played a role in getting Brink the ambassador job.

Other hardline pro-government media in Ukraine have reported that Brink has an excellent relationship with Nuland, heralding her past work in Georgia, another state fighting off the Russian Bear, and observed that Brink perhaps had limited command of the Ukraine conflict itself—but that’s of little concern because of her choice alliances in Washington.

The day of Nuland’s resignation, Brink posted on X, “Deep thanks and respect to Under Secretary Victoria Nuland. She spent her career defending freedom and democracy. Her values-based diplomacy served the U.S., Ukraine, and the world, setting the example for a generation of American diplomats. We are proud to continue her legacy.”

Brink’s employment of the term “values-based diplomacy” would seem a clear jab at realist and restrainer perspectives that value ending the war over a hawkish commitment to regime change in Moscow, and, at the very least, would seem out of step with the new sheriffs in town in Washington.

The association is clear. Nuland and Brink started working on Ukraine very closely a decade ago—in the Obama presidency. As a fellow traveler of Nuland, Brink became the deputy assistant secretary in the European bureau with responsibility for six countries including Ukraine. During this time, Brink reported to Nuland and worked with her and others to formulate U.S. policy on Ukraine.

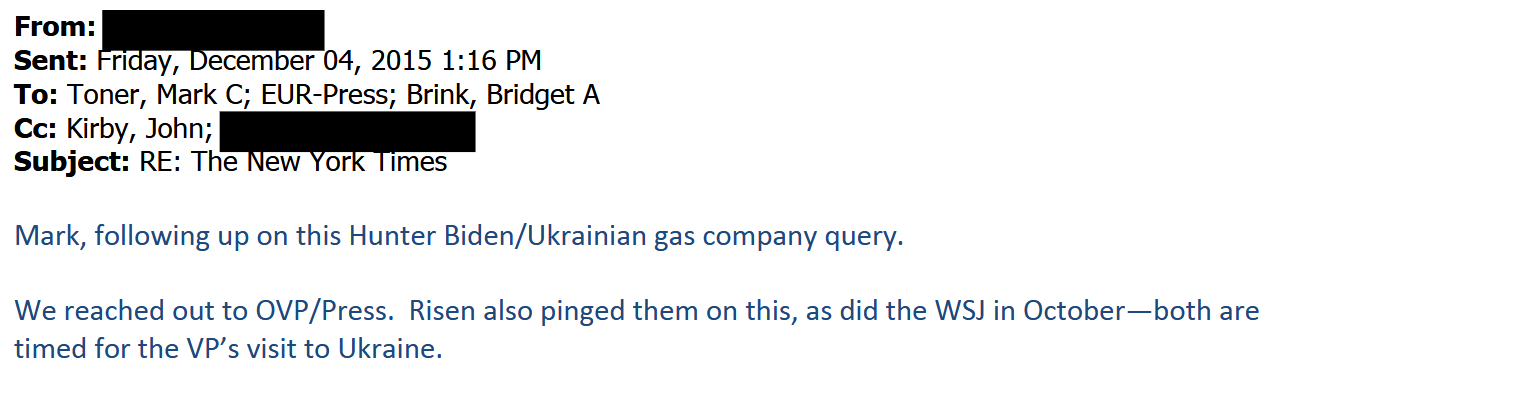

Most dangerous and partisan for Brink’s tenure is her potential enmeshment with the Hunter Biden imbroglio—or so say some detractors in Marco Rubio’s new State Department.

In 2014, Hunter Biden joined the board of Burisma Holdings, a Ukrainian natural gas company. The younger Biden’s role lasted until 2019. Hunter is reported to have advised on corporate governance and transparency. At the time, Burisma was under investigation over its founder, Mykola Zlochevsky, a former Ukrainian government minister accused of corruption during his tenure (allegations he denies).

During this time the Obama administration, including then–Vice President Biden, supported anti-graft reforms in Ukraine. There was pressure to remove officials perceived as corrupt, such as Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin. Nuland aggressively pushed efforts to oust Shokin from his position of power. “So by the time we get to December of 2015, we concluded that [Ukraine] is not going to get cleaned up under Shokin and that there needs to be—and to encourage Poroshenko to demonstrate his commitment by replacing Shokin,” Nuland has testified.

Joe Biden has publicly acknowledged urging Ukraine to fire Shokin, citing concerns over Shokin’s failure to pursue corruption cases, including those involving Burisma. Critics have alleged Biden sought to protect his son with these actions. Regardless, the cavalcade of outlandish personal and financial scandals eventually exposed Hunter Biden to federal prosecution and conviction. (Biden pere, as president, subsequently pardoned his son.)

While evidence is far from conclusive, there is concern that Brink was part of the inner circle of Department of State staff that coordinated the-then Obama administration’s response to the Burisma matter.

Brink is no one-sided Democrat. She was appointed to roles by Donald Trump in his first administration, including as ambassador to Slovakia (which today is one of the most dovish EU countries on the Russia–Ukraine conflict). But Trump has fallen out with all manner of officials from establishment Washington, including dozens of former officials from his cabinet and presidential campaigns.

And with the changed tone set by his second administration, on full display last week with Zelensky, many are left to wonder whether the new government will turn the page on the past—and if Brink’s time is up.

Read the full article here